The Sanborn fire insurance maps hinted at a building that would make a great model: tall (30'), multiple floors for processing fruit, additions (sulphur box on the second floor), and a boiler and oil tank along San Carlos St. Model railroads need lots of industries to ship enough cars to make an operating system fun, and this place looked like the kind of shipper I needed on my railroad - busy, rambling, and photogenic.

The Vasona Branch is modeling 1932, but at the time I didn't know whose name should be on that building. I flipped a coin, anointed Abinante and Nola the current owner, built my model, and many crews have carted boxcars of dried fruit from the place ever since.

But I was still curious about Abinante and Nola. What did the building really look like? How did the dried fruit packing business work?Luckily, I started trading e-mails with Don Abinante and Vincent Nola, sons of the founders, and learned a bunch about dried fruit packing. Here's a quick history of Abinante and Nola, and some quick notes on what the business was really like (as opposed to how it appears on the

model railroad.)

Abinante and Nola's History

Abinante and Nola actually was founded around 1932 or so, out in a barn on the Nola ranch on Berryessa Road west of I-680. Sam Abinante, raised in Cupertino and San Jose (Stevens Creek Road) was a fruit buyer and knew the sales processes and the brokers who sold the fruit to wholesalers on the east coast and abroad. Frank Nola had been managing his mother's fruit ranch on Berryessa Road, and knew the production side. It was a crazy time to enter the market; the Great Depression had caused markets to collapse. The Hunts Cannery in Los Gatos stayed dark in 1931 and 1932 because of the business climate. I don't know why they started the business, but I could imagine that selling their own crop and crops of neighbors could get them more money than trying to go through the existing packing houses.

Their new business flourished. By 1935, they'd managed to save some of the profits, and moved off the Nola ranch and into a new plant on Stevens Creek Road near Cupertino, next to the Abinante family ranch. The building had been the former West Side Cooperative Dryer property, located a couple blocks away from the current Nissan dealership. (If you're eager for exact location, let's guess at Woodhams Road between Lawrence and San Tomas Expressways.)

The loss almost made Sam give up on the business, according to his granddaughter. The war in Europe certainly didn't provide hope that the European markets were going to improve any time soon. However, they decided to keep going; a 1940 issue of Engineering News-Record notes the request for bids for the new warehouse to replace the burned plant in September, 1940, but I get the impression that they decided not to rebuild at the same site. The family said that the business returned to the Nola ranch; they built a new barn, got a new grader and warehouse, and processed apricots and pears. They also also acted as brokers for fruit processed by others: Valley View Packing (run by the Rubino family down on Hillsdale Ave. near the Guadalupe River) and California Packing Corporation (Del Monte.) They got rid of the Westside dryer property after the fire; the Verbaccia family next door bought the land, cleaned up the property, and used it for farming til suburbia invaded.

But the Nola Ranch wasn't big enough for the business, so they started looking for more warehouse and packing space. Sam and Frank bought the a new plant at 236 Ryland Street from the failing Winchester Dried Fruit Packing Co. That plant, a turn-of-the-century packing house, was just across the tracks from the old San Jose Freight Depot near Bassett Street and San Pedro St. A 1944 San Jose city building permit notes the foundation work that the old building needed. Ryland Street served primarily as the processing plant (with some storage out at the ranch), and gave the business rail access for the U. S. east coast markets. Vincent remembers driving on Sunday evening with his dad to check that the Southern Pacific had delivered the two or three cars they'd need to load the next day.

In the late '40's, Abinante and Nola finally moved to that building that I model at 750 West San Carlos St from J.S. Roberts. J. S. Roberts had been active in the San Jose fruit packing business for at least twenty years, but had just gone out of business. Frank really liked this plant; there was plenty of space for loading and unloading, lots of room for trucks to wait on the side street without blocking traffic (thanks to the San Carlos St. viaduct above), and a huge amount of storage space for storing the year's crops. It also had more modern grading equipment than Ryland St. There was also a Southern Pacific spur for rail traffic. They kept the building on Ryland Street, both as extra storage for the unsold dried fruit, and also for packing cherries from the Nola ranch.

Abinante and Nola also started a separate cannery for reconstituted prunes and prune syrup. They mostly did this for breadth; some of the brokers buying their dried fruit would ask "and do you have canned prunes too?" and they wanted to be able to get some of this business as well. The canning plant was at 345 Sunol St., just behind O. C. MacDonald. The business was always small, and Abinante and Nola eventually sold it to Stapleton and Spence.

Around 1950, Frank Nola decided he needed a break, and decided to retire from Abinante and Nola and instead focus on the family ranch. Sam Abinante, his son, and his son-in-law ran the business. Within a few years, they bought Mayfair Packing's former Plant #2 at 631 Sunol St. Mayfair was one of the larger independent packers in the San Jose area, and had just moved to their new, modern plant on South Seventh Street near the county fairgrounds, and Abinante and Nola got a newer, more modern site. The new plant was on the Western Pacific, and a late 1950's WP track diagram in Track and Time marks the building as Abinante and Nola. That building still stands, by the way, occupied by a roofing supply house at a new addresss of 991 Lonus St.

By 1966, though, the encroaching suburbs were eating up the remaining prune orchards in the Bay Area, and the fruit to pack was often coming from the Sacramento Valley. Abinante and Nola moved to a modern prune processing plant in Fairfield to be closer to the Yuba City farmers supplying the fruit, and thus leaves our story.

The Business

Abinante and Nola's primary business was packing prunes, but they also handled smaller amounts of dried apricots, peaches, and pears. The business produced a good quantity of fruit - typically around five or six million pounds a year.

To understand what Abinante and Nola's packing houses was like, Sunsweet's 1950 video gives a good overview of the dried fruit packing business.

Early in the year, each packing house would visit the farmers who they worked with, and offer the farmers a price for their crop based on the graded size of the prunes. They might offer 8 cents a pound for 30/40 (thirty to forty dried prunes per pound), 6 cents for 40/50, less for the smaller fruit, and little or nothing for the damaged or odd-shaped fruit. The buyer set the price based on guesses about the likely crop size, the farmer's typical crop, and expected prices for the next year. There wasn't much bidding and competing between the packing houses; the farmers tended to stick with the same packers each year as long as they were treated honest and fairly. Larger ranches gravitated to the larger packers; Abinante and Nola tended to attract the smaller ranches with smaller amounts of fruit. Their relationship and rapport with the fruit ranchers was one of the selling points. "If you sold to Guggenhime, you weren't talking to Mr. Guggenhime, but if you went to Abinante and Nola, you'd be talking with one of the owners."

The prunes would ripen in mid summer. Farmers would dry the fruit before delivery, either in their own drying yard or at a commercial dryer. When the fruit first went to the dryer, it would be washed, then run through the dehydrator to reduce the water content and preserve the fruit.

The dried fruit would start appearing at the packing houses around mid-August, delivered in sacks (in early days) or in 2000 pound wooden containers (later years) to the fruit packer. The farmers would pick up their fruit from the dryers, haul it over to the public scales at the Security Cold Storage Warehouse for weighing, then truck the fruit over to Abinante and Nola's plant. (The building was always referred to by the folks I talked with as "the plant.") The fruit would be offloaded, hauled onto the ubiquitous freight elevator in the packing house for a ride to an upper floor, then sent to the grading machine for sorting by size. The fruit would then be put in wheelbarrows, and dropped down into the storage bin for each size. The grade sheet would list how many pounds of fruit went to each grade, and they'd figure out a final price for the crop. Abinante and Nola then held the sorted fruit in storage until sales came in.

Packers generally sold the fruit bit by bit over the year, so the packing house needed enough storage space to hold the full year's crop. When the orders came in, the packers would pull fruit of the desired size out of the storage bins, relying on gravity for most of the movement. In the early days, the fruit might only get sacked upon purchase. Abinante and Nola started selling their prunes in 100 kilo sacks. The sacks would be taken to San Francisco's piers or Alameda's Encinal Terminal, and put on ships for Europe. Their Bay Area location must have simplified the process of exporting crops to Europe, especially when they didn't have a railroad siding. Vincent Nola remembers the sacks of prunes destined for Germany in the barn on Berryessa Road: "fine, tough burlap bags with big green stripes across them". The Great Depression and trade restrictions by Germany cut the Europe trade by the late 1930s.

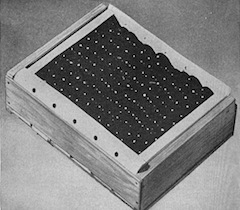

In later years, the fruit to be sold would be pulled out of the storage bins, inspected by women working the inspection lines, washed in hot water, and steamed for easier processing and sanitizing. It would be inspected again, and re-hydrated to 20% humidity for consistency. Men would pack the 25 pound boxes (wood in the 1930s, cardboard the 1950s), run them past a final check station, put on the lid, then stack the boxes for the clamp truck. Dried apricots, peaches, and pears had an additional trip through the sulphur boxes to lighten the color before packaging. Men always did the warehouse and boxing; women always worked the inspection and sorting lines. The Sunsweet video shows the fruit being boxed for individual sale, but Abinante and Nola were processing for wholesale distribution. In the 1930s, they exported the fruit to Europe and even Cuba. As time went on, they started selling to brokers and retailers on East Coast, Chicago, and Texas as well. When the company shipped product to the east coast in the 1950s, it would tend to go via rail, and they'd ship only two or three cars a month.

Abinante and Nola wasn't the only dried fruit packer in the valley. Mayfair Packing and Valley View were two other privately held fruit packers, and were considered "friendly competitors" by Abinante and Nola-not cutthroat, but each company had to be aware of the other's prices when purchasing fruit from farmers and when selling to the brokers. Guggenhime & Co (which had plants over by the San Jose Market Street Station) handled both dried and fresh fruit, but was a smaller competitor. The big producer-then and now-was California Prune and Apricot Growers (Sunsweet); they had a major effect on prices, but tended to sell into retail and didn't compete directly with Abinante and Nola.

Sunsweet still dominates the industry; check out the Prune Barganing Association's history to see how 60% of prunes are still sold through Sunsweet.

I'd assumed that canners would have been competing for the same fruit, but each crop and farmer tended to specialize in either fruit for drying or canning. Del Monte, Stapleton and Spence, Filice and Perelli, and Rosenberg Brothers were primarily canners, and did not compete with Abinante and Nola. Although Del Monte had a bit of a dried fruit business, they didn't cross paths with Abinante and Nola because of the size of the market and the fact that Del Monte was processing for their own label.

The Plants

Abinante and Nola had occupied packing plants in the San Jose area at different times:

- the Nola ranch on Berryessa Road on the east side of the Santa Clara Valley

- the Westside Dryer plant out on Stevens Creek Road

- 236 Ryland St., the former Inderridden and Winchester Dried Fruit plant,

- 750 West San Carlos St, the former J. S. Roberts and Pacific Fruit Packing plant, and

- 631 Sunol St., former Mayfair Packing Plant #2

Some of the buildings on the Nola ranch still exist (but soon will be replaced by houses), and 631 Sunol, now a roofing supply company, is still standing.

West Side Cooperative Dryer site, Stevens Creek Road, Santa Clara

“West Side”, better known now as Cupertino, was a center of fruit growers from early on. In 1891, the local farmers incorporated the West Side Fruit Growers Association co-operative to dry their fruit and the sell it on the open market. "Sunshine, Fruit, and Flowers", states that they processed 3,650 tons of prunes, apricots and peaches in 1893, cutting the fruit and drying it on drying flats in the sun. The co-operative was on the North side of Stevens Creek Road near the current Woodham's Road. The West Side co-op merged with the County Fruit Exchange, which eventually disbanded in 1916.

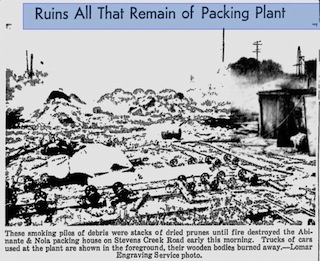

By the mid 1930s, the property was available again, and Abinante and Nola occupied the property. I don't know what buildings were on the property at the time, but the historic photos of the West Side Dryer hint at its appearance. In 1940, Abinante and Nola built a new warehouse on the property. In the mid '40's, the plant disappeared in an arson fire, and Abinante had to move again.

236 Ryland St., San Jose

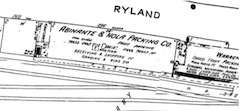

Around the time of the fire at the West Side Dryer plant, Abinante and Nola took a new building just north of downtown San Jose around the Southern Pacific's freight depot. Ryland Street was the first street just north of the tracks, named for C. T. Ryland, an early resident of San Jose. His house had been at First Street near the railroad tracks, but now is the site of Ryland Park and Pool. Ryland St. ran two blocks west past the park, finally ending at the Guadalupe River; the south side of the street had the warehouses bordering the railroad yard, and the north side of the tracks - the edge of the Vendome neighborhood was a working class hispanic neighborhood at the time.

Abinante and Nola's new building was in a long row between San Pedro Street and the river. In 1950, the building at the corner of San Pedro and Ryland was a beer distributor (formerly Farmers Union warehouse, and before that Alber Brothers Milling), then Warren Dried Fruit, run by Jimmie Schneider (who also was working the mercury mines at New Almaden, and wrote one of the books about New Almaden history. Next came Abinante and Nola's plant, and then the Teresini Brothers metal recycling. Teresini Brothers highlights an interesting part of the cannery business. During the season, the canneries weren't always sure what sizes would sell, so they would can fruit in very large cans, then open and re-can the product in smaller cans if necessary. Teresini Brothers bought the scrap cans for recycling.

A&N’s new building, 236 Ryland, had its own string of owners. It had been used by Inderridden, a Chicago-based grocer and packer at the turn of the century, at least from 1905 to 1915, had held Rosenberg Brothers for a while, and in the late 1930s had been Winchester Dried Fruit Co.'s packing plant. Winchester was run by Bert Kirk and Antonio Teresi, part of the Kirk family (who owned a large ranch near Dry Creek Road in San Jose), and Teresi family which ran the former Sorosis fruit ranch near Saratoga. Winchester had gone bankrupt at some point in the 1940s, and lawsuits over condition of sold fruit suggest they may have been having problems earlier according to some of the lawsuits that turn up when searching Google on the company name.

236 Ryland was wood with a truss roof, two stories high, and 200 feet long and 50 feet wide according to an SP valuation map, and 24 feet high at the eaves according to the Sanborn map. Like many dried fruit plants, its primary purposes were grading, storing, and packing. Trucks could unload on Ryland Street; the fruit from the dryer would be hauled in the elevator up to the second floor for grading, then dumped into the storage bins to await sale. Upon sale, the fruit would be pulled out of the bins on the first floor, washed, inspected, and packed. The required boiler for hot water was on the front door - straight through, past the office, and almost to the railroad dock. The boiler sat at ground level while the rest of the building was raised four feet to match the rail cars.

The loading dock looked out over the former San Jose railroad yards - a busy place when the main line ran down Fourth Street to Los Angeles, but quieter now that the main line went around the West side of town. Across the tracks sat the 1870s era Southern Pacific Freight Depot, and beyond that was the north side of downtown, Guggenhime's dried fruit packing plant, and the Eggo Food Products factory making waffles.

Vincent Nola remembers it as an old building. He remembers helping out on the packing line during cherry season when they were short of help. Don Abinante just remembers it as the place he tipped a forklift over.

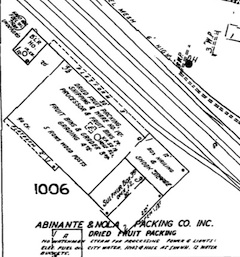

750 West San Carlos St., San Jose

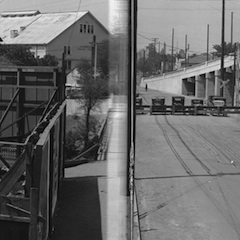

Towards the end of the 1940s, Abinante and Nola bought J. S. Roberts' old packing plant off of San Carlos Street just west of downtown. This neighborhood was another hotbed of the Valley fruit processing, with the huge Del Monte plant, Contadina, U. S. Products, Mayfair Packing Plant #2, and many other fruit-related businesses within a couple blocks. Near the site was O. C. MacDonald (a local plumbing contractor), Cheim Lumber, and a bunch of small businesses. Across the street was a bar and restaurant and liquor store that probably catered to the workers coming off-shift at all the canneries and packing houses.

The new building sat just underneath the San Carlos Street viaduct which crossed (in sequence) Dupont Street, the old San Jose - Santa Cruz (South Pacific Coast) railroad tracks, the new Southern Pacific main line to Los Angeles, and finally the Guadalupe River. With traffic whizzing by on the viaduct, the old San Carlos Street was now much quieter, with room for the trucks to park before going to the plant’s loading dock to unload.

According to the Sanborn maps, 750 West San Carlos St. was massive - four stories tall. The top floor was for grading and storage. The third floor stored the unprocessed fruit waiting to be sold. The second floor had the processing machinery and the sulfur box for re-treating apricots just before packing and sale. The first floor was for packing, storage of finished product, and the office. Separate from the main building and out by San Carlos St was the small boiler house for the hot water and steam and an underground 6000 gallon tank. That's a big tank - think eight feet in diameter and sixteen feet long. The boiler house was also photogenic, hidden behind a fence and various weeds, and sheathed in corrugated iron. The San Carlos St. building is gone now; Historic Aerials shows the building disappeared some time between 1948 and 1956.

Vincent Nola remembers it as a huge old building - four floors, three that were very large, and dark inside. "I'd have painted it all white if it were up to me." Again, a large freight elevator was needed to carry up the incoming fruit up to the grader. Like the Sanborn map shows, the sulphur box for processing the apricots, peaches, and pears was on the second floor as an addition leaning out over the South end of the building. The boiler-outside-was used for reconstituting the fruit back to 20% moisture.

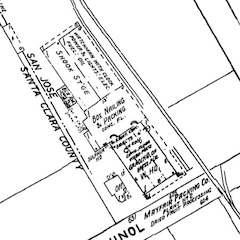

631 Sunol St., San Jose

Abinante and Nola's last dried fruit plant in San Jose was the former Mayfair Packing plant on Sunol St. Mayfair was one of many success stories in the Santa Clara Valley, founded in 1931 by Joseph Perucci, and starting out on the East side of San Jose in the Mayfair neighborhood. They occupied the plant on Sunol Street from at least the early 1940s and possibly earlier. In 1948, they acquired the old Bisceglia Brothers plant on South First Street for their Sun Garden label, and eventually moved to a large, modern plant on South Seventh Street. That plant still has the Mayfair logo painted on a water tank in the front of the plant. Mayfair must have wanted to move out of the plant on Sunol St earlier.; a newspaper article showed that they tried to sell the operation in 1942, but Homer Hamlin and R. S. Butler, who were renting the attached drying yard, protested.

Abinante and Nola took around 1950. This plant was also on a rail line for easier shipping (though now on the Western Pacific rather than the Southern Pacific). The building was single story with a clerestory roof, long and low. It was divided into a front, center, and back section. The front section held the warehouse with the grading equipment on a mezzanine, box nailing and packing in the middle (along with a sulphur house on the side away from the railroad), and shook (box) storage in the back section. Like the other plants, a boiler room was attached to the side of the building, and a separate office was in what I suspect was a converted house on the front of the property.

The Model

So that's what I know about Abinante and Nola. The building with their name on it on the Vasona Branch was theirs only for a few years, and if I were more earnest, I'd change the name to J. S. Roberts, the actual occupant in 1932. But I like it, and now that I've learned about Abinante and Nola, I'm not too interested in correcting the anachronism.

All this research also hints that I might need to run the layout differently. For the sake of argument, let's assume that the business would have been run the same way by the building's occupant in 1932.

- I should consider loading fewer freight cars at Abinante and Nola. With most fruit going to Europe, I ought to have fewer east coast boxcars loading there, and either direct more fruit out in SP boxcars (for traffic being sent to the piers) or cut the total number of cars and put more trucks in the scene.

- Ship fewer cars. I set my layout during a fruit rush (either early for apricots or later for other crops), but because Abinante and Nola was shipping continuously during the year, it wouldn't have been the same beehive of outgoing activity that I would have seen in the canneries.

- Don't bring tank cars to Abinante and Nola. Because of the size of the oil tank, it's unlikely they would have gotten oil via rail. I'll bet the oil dealer would have stopped by every few weeks to top off the tank.